The biological imperative of a startup is to grow. Similar to how reproduction perpetuates the existence and survival of a species, growth brings about the continued existence and survival of a startup.

Initially, this search for growth manifests itself as a search for traction — succinctly defined by AngelList co-founder Naval Ravikant as “quantitative evidence of customer demand.”

At their earliest stages then, startups set out to prove that a market need exists for their product or service. Oftentimes this is the realm of ‘growth hacking’ and “doing things that don’t scale”; of experimentation, discovering what works and doubling down on it.

The Bible, in the third chapter of Ecclesiastes, advises that to everything there’s a season. And this is also true for startups: there’s a time for execution and a time for strategy. And at the stage where new ventures are earnestly searching for traction, execution is paramount.

At some point, however, the challenge is no longer about getting a product or service off the ground. Once its proven that commercially viable customer demand exists, the focus moves to achieving the next phase of growth. It’s here that startups can enjoy great benefits from carefully considered growth strategy.

Consider, for example, Nigerian supply chain logistics platform TradeDepot’s foray into the provision of credit facilities to its informal retailer customers, or Nigerian healthcare data management and medical billing startup Helium Health’s post-Series A launch of CareCredit, a digital loan product for healthcare providers. Having proven an ability to execute and to serve a core market with a core product, both ventures made choices in search of growth that evince an underlying strategy. After all, strategy is choice.

But how do, or how should, startups at this stage evaluate different options for growth?

One effective but perhaps lesser-known framework (certainly in the world of startups) comes from Russian American mathematician Igor Ansoff, the so-called ‘father of strategic management.’

In his 1957 Harvard Business Review article, ‘Strategies for Diversification,’ he wrote: “There are four basic growth alternatives open to a business. It can grow through increased market penetration, through market development, through product development, or through diversification.” While Ansoff’s writing is equally applicable to later-stage businesses, growth is the stuff startups are made of, and as such his ideas are particularly relevant.

For Ansoff, the interplay between products and markets is the key to understanding distinct paths companies can take towards growth. Notably, for him, a market isn’t based on geography or other customer characteristics, but rather on what would best be identified today as the late Clayton Christensen’s jobs-to-be-done concept.

A half-decade before Christensen, Ansoff wrote, “In thinking of the market for a product we can borrow a concept commonly used by the military — the concept of a mission. A product mission is a description of the job which the product is intended to perform … For our purposes, the concept of a mission is more useful in describing market alternatives than would be the concept of a ‘customer,’ since a customer usually has many different missions, each requiring a different product.”

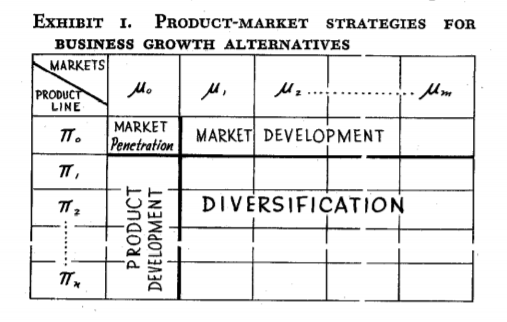

Ansoff originally visualized his idea as a product-market matrix where “π represent[s] the product line and µ the corresponding set of missions.”

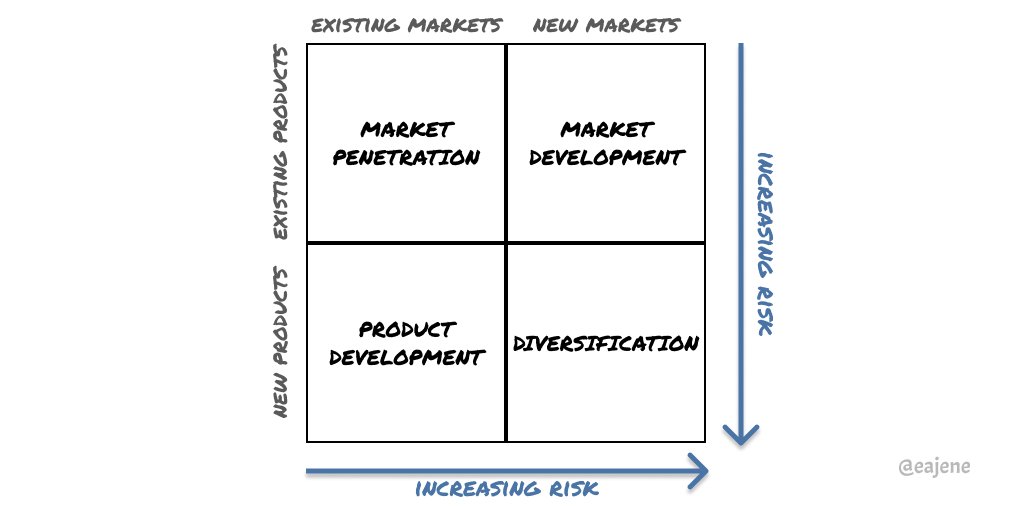

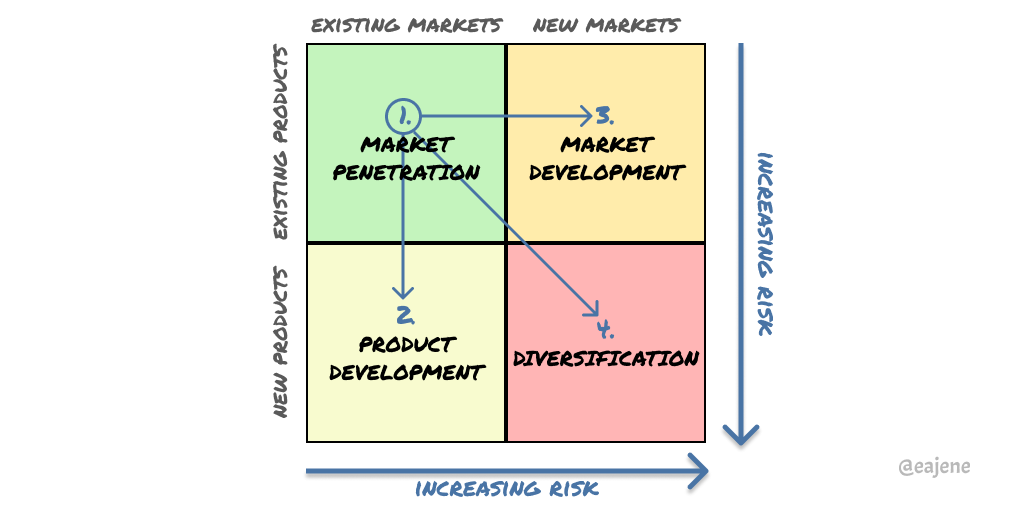

Today, strategists simplify this into four quadrants and overlay arrows representing risk.

So, to recap, startups first find traction by serving core markets with core products, then they are confronted with the question of how best to seek further growth.

Ansoff’s matrix provides a powerful framework to evaluate the options for future growth. The question for startups becomes (1) whether to focus on penetrating the existing market more deeply and gaining greater market share, (2) whether to offer additional products and services to the existing customer base, (3) whether to offer the existing product to new markets (i.e., propose it for new missions or jobs-to-be-done), or (4) whether to offer entirely new products to new markets.

The four options

- Market penetration,

- Product development,

- Market development, and

- Diversification

are listed from least risky to most risky as companies move from their core capabilities to adjacent products and markets then finally beyond their zone of competence altogether.

Ansoff defined a market penetration strategy as “an effort to increase company sales without departing from an original product-market strategy.” Here, the firm grows by selling more of its existing products to existing customers and by finding new target customers to sell existing products. Often this is done by increasing advertising, optimizing sales & distribution channels, and/or acquiring a rival in order to access new customers; or relying on loyalty programs, promotions & special offers, and/or excellent customer service to retain and up-sell existing customers. Think, for example, of payment platforms Paystack or Yoco increasing their market share among SMEs in Africa.

For Ansoff, a product development strategy “retains the present mission and develops products that have new and different characteristics.” In other words, this involves growth via the creation of new products to serve existing customers, markets, and jobs-to-be-done. Think now of the examples of TradeDepot and Helium Health mentioned above as both firms offered new credit products to existing customers.

On the other hand, Ansoff defines a market development strategy as one in which “the company attempts to adapt its present product line to new missions.” That is to say, the company grows by selling existing products (with minor modifications) to new customers/markets or adapting existing products for new jobs-to-be-done. Think here, for example, of Nigerian e-learning platform uLesson’s relatively early geographical expansion outside of Nigeria. Or think of B2C companies that have moved to offer their existing products to new B2B markets within the same geographic locale.

Finally, Ansoff describes a diversification strategy as “standing apart from the other three … a simultaneous departure from the present product line and the present market structure.” In this scenario, a company sheds its past to serve new markets and customer needs with new products. These may be game-changing, last-effort ‘hail-mary’ pivots, or bets on a particular vision of the future by developing new products and services to serve currently non-existent or immature markets. Think here of GTBank, the staid multinational bank, launching all-in-one e-commerce / news & entertainment / lifestyle super app Habari.

At the end of the day, Ansoff’s matrix doesn’t prescribe a specific growth strategy. Its power comes from the manner in which it encourages leaders to explore various courses of action in relation to a company’s existing markets/customers and existing product/service offerings. This exercise, done with risks, uncertainties, and company resources in mind, helps startups make the best individual decision for growth.

For some in a new uncontested market, success may lie in rapidly growing market share via a market penetration strategy, while others may find success in taking on more audacious diversification risks with the chance for bigger payoffs. While all this may seem obvious, few startups explicitly consider their best strategy for growth, and Ansoff’s matrix can offer unique insights in this regard.

Interested in applying growth strategy frameworks to your business? Africreate is a thinking partner to leading startups, corporates, and investors across African markets.

Share: